Rank and Name, Private First Class Edgar H. Carter.

Unit/Placed in, 59th Coast Artillery Regiment, United States Army.

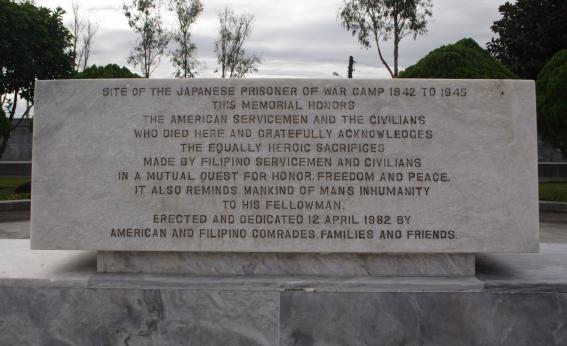

Camp Cabanatuan(Pangatian) (former HQ 91st Philippine army Division)

After the Japanese occupation in 1942, the camp was converted by the Imperial Japanese Army into the Cabanatuan POW Camp. At its height, 8,000 prisoners were detained at this location. The prisoners also included some civilians including one British and one Norwegian citizen. This POW Camp detained prisoners until liberated during the night of January 30, 1945.

The rectangular camp spanned roughly 25 acres and was 800 yards deep by 600 yards wide, divided by a road in the center. The camp consisted of a barracks for Japanese guards, barracks for prisoners, a hospital and water tower enclosed by barbed wire with guard towers.

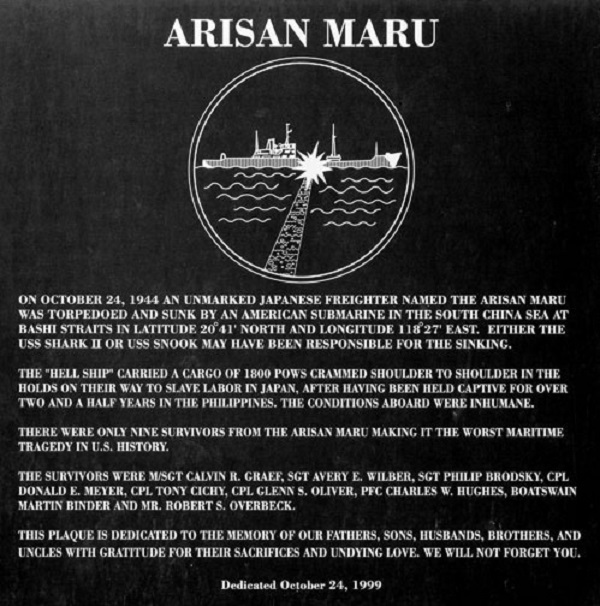

Arisan Maru

The Arisan Maru was a Hell Ships (former Cargo, used for Transport POW’s to other Camps) sunk on Nov. 24, 1944.

The Arisan Maru, sailed from Manila on October 11, 1944 for Japan. This ship was sunk by the American submarine, USS Shark with three torpedoes, on November 24, 1944. There were 1800 POWs aboard – nine men survived this sinking. Two days later, five of the survivors were rescued by a Chinese fishing junk. The Chinese helped them reach American Air Corps forces. Other survivors were recaptured by a Japanese destroyer and taken to Formosa.

This Hell Ship sank in the South China Sea making it the worst naval disaster in the history of the United States.

Edgar is born approx. on 1911 in Putnam County, Georgia.

Mother, Martha Rebecca (Branam) Carter.

Sister(s), Eva Garnell, Julia and Aileen Carter.

Brother(s), Clifford L. Carter.

Edgar enlisted the service in Fort Benning (Georgia) on 18 February 1941 with service number # 14045153.

Edgar was KIA/MIA when he went to on transport to a POW Camp in Japan aboard the “Hellship Arisan Maru” which was Torpedoed by the USS Shark in the south China Sea when he tried to escape he got shot on 24 Oktober 1944, he is honored with a Purple Heart, POW Medal, Good Combat Ribbon, Good Conduct Medal, American Campaign Medal, Asiatic Pacific Campaign Medal, WW II Victory Medal.

Edgar is buried/mentioned at Manila American Cemetery and Memorial Manila, Metro Manila, National Capital Region, Philippines.

Walls of the missing.

Thanks to,

Jean Louis Vijgen, ww2-Pacific.com ww2-europe.com

Air Force Info, Rolland Swank.

ABMC Website, https://abmc.gov

Marines Info, https://missingmarines.com/ Geoffrey Roecker

Seabees History Bob Smith https://seabeehf.org/

Navy Info, http://navylog.navymemorial.org

POW Info, http://www.mansell.com Dwight Rider and Wes injerd.

Philippine Info, http://www.philippine-scouts.org/ Robert Capistrano

Navy Seal Memorial, http://www.navysealmemorials.com

Family Info, https://www.familysearch.org

WW2 Info, https://www.pacificwrecks.com/

Medals Info, https://www.honorstates.org

Medals Forum, https://www.usmilitariaforum.com/

Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com

Tank Destroyers, http://www.bensavelkoul.nl/

WordPress en/of Wooncommerce oplossingen, https://www.siteklusjes.nl/

Military Recovery, https://www.dpaa.mil/

DEATH MARCH

Following the surrender of Bataan on April 9, 1942, to the Imperial Japanese Army, prisoners were massed in Mariveles and Bagac town.

As the defeated defenders were massed in preparation for the march, they were ordered to turn over their possessions.

Word quickly spread among the prisoners to conceal or destroy any Japanese money or mementos, as the captors assumed it had been stolen from dead Japanese soldiers.

Prisoners started out from Mariveles on April 10, and Bagac on April 11, converging in Pilar, Bataan, and heading north to the San Fernando railhead.[3] At the beginning of capture there were rare instances of kindness by Japanese officers and those Japanese soldiers who spoke English, such as sharing of food and cigarettes and permitting personal possessions to be kept. This was fast followed by unrelenting brutality, theft, and even knocking men’s teeth out for gold fillings, as the common Japanese soldier had also suffered in the Battle for Bataan and had nothing but disgust and hatred for his “captives” (Japan did not recognize these people as POWs).[4] The first atrocity—attributed to Colonel Masanobu Tsuji—occurred when approximately 350 to 400 Filipino officers and NCOs under his supervision were summarily executed in the Pantingan River massacre after they had surrendered. Tsuji—acting against General Homma’s wishes that the prisoners be transferred peacefully—had issued clandestine orders to Japanese officers to summarily execute all American “captives.”Though some Japanese officers ignored the orders, others were receptive to the idea of murdering POWs.[12]

During the march, prisoners received little food or water, and many died.[2][13][14] Prisoners were subjected to severe physical abuse, including being beaten and tortured. On the march, the “sun treatment” was a common form of torture. Prisoners were forced to sit in sweltering direct sunlight, without helmets or other head covering. Anyone who asked for water was shot dead. Some men were told to strip naked or sit within sight of fresh, cool water.[8] Trucks drove over some of those who fell or succumbed to fatigue, and “cleanup crews” put to death those too weak to continue, though some trucks picked up some of those too fatigued to continue. Some marchers were randomly stabbed by bayonets or beaten. The Death March was later judged by an Allied military commission to be a Japanese war crime.

Once the surviving prisoners arrived in Balanga, the overcrowded conditions and poor hygiene caused dysentery and other diseases to spread rapidly. The Japanese did not provide the prisoners with medical care, so U.S. medical personnel tended to the sick and wounded with few or no supplies.[13] Upon arrival at the San Fernando railhead, prisoners were stuffed into sweltering, brutally hot metal box cars for the one-hour trip to Capas, in 43 °C (110 °F) heat. At least 100 prisoners were pushed into each of the trains’ unventilated boxcars. The trains had no sanitation facilities, and disease continued to take a heavy toll on the prisoners.

Upon arrival at the Capas train station, they were forced to walk the final 14 km (9 mi) to Camp O’Donnell. Even after arriving at Camp O’Donnell, the survivors of the march continued to die at rates of up to several hundred per day, which amounted to a death toll of as many as 20,000 Filipino and American deaths. Most of the dead were buried in mass graves that the Japanese had dug behind the barbed wire surrounding the compound. Of the estimated 80,000 POWs at the march, only 54,000 made it to Camp O’Donnell.

The total distance of the march from Mariveles to San Fernando and from Capas to Camp Cabanatuan or O’Donnell (which ultimately became the U.S. Naval Radio Transmitter Facility in Capas, Tarlac; 1962-1989) is variously reported by differing sources as between 96.6 and 112.0 km (60 and 69.6 mi).

Thanks To Wikipedia